The Leaky Pipeline: Why Don't New Teachers Teach?

In Tennessee in 2012-13, the state’s tracking system found that only about half of those graduating from teacher preparation programs entered the teacher workforce the following year. Delaware’s brand new tracking system showed in-state placement rates of about 28 to 65 percent.

So what happened to all those other graduates—the ones who completed teacher preparation and didn’t start teaching?

This is an important question to try to answer now. This year, school leaders in states say they can’t find the hundreds of teachers they need to lead classrooms. Yet, according to some data, we overproduce teachers, preparing many more than there are jobs.

Can both things be true?

Perhaps the problem is that there’s precious little data on what may be the teacher pipeline’s leakiest section—after teacher candidates complete their preparation program and before they start their first jobs.

Most states don’t track that data. And the few studies or surveys that follow graduates into the classroom tell a disturbing story: Between a quarter and a half of those who complete a teacher preparation program don’t end up teaching after graduation.

Every state is different, of course, but Tennessee has some of the best state employment data on graduates of its teacher preparation programs. That gives us a bead on what happens to teacher candidates between graduation and entering the workforce.

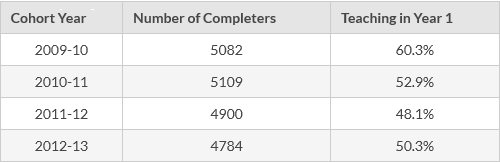

Table 1. Percentage of teacher preparation graduates entering teaching in Tennessee

Some states hire a great many teachers from out of state. A recent article in Education Week reports that in 12 states, half of the certificates issued to new teachers go to ones trained out of state. There’s a caveat here. Graduates from Tennessee teacher preparation programs might have taken jobs in private or charter schools or out of state, making it hard to keep tabs on these graduates.

Or graduates might decide to take a year or two off to do something else before teaching—whether joining the Peace Corps, getting a master’s degree, or just taking a year off. These graduates would be counted as “not teaching,” even if they join the teacher workforce a few years after graduating.

A national study that followed graduates into the workforce found that of the 11,000 college graduates surveyed in 1993, 13 percent (1,430) were education majors. In a follow-up a decade later, 29 percent (415) said they had never taught after graduating and less than half (636) of those education majors were still working in education.

Yes, the teacher pipeline had leaks even 25 years ago when it had swelling enrollments. But what’s different now is a national 30% drop in enrollment in teacher preparation programs from 2009-10 to 2012-13. So filling the gap between the number of graduates and the number of new teachers who enter the workforce may be one option for states trying to relieve teacher shortages.

Policymakers and teacher preparation educators should be asking: Do we know where our graduates end up? Why are so many graduates not entering teaching? Are we keeping students in teacher preparation programs who have discovered that they never want to teach? How can we attract the right people into teacher preparation, and help them move into the classroom after graduating?

Program graduates’ reluctance to enter the teacher workforce may begin with their student teaching experiences. Plenty of anecdotal evidence suggests that teacher candidates are unprepared for the hard work of student teaching that comes at the very end of their preparation program. A possible reform would be getting teacher candidates into classrooms much earlier—say, in the first year of their program.

Many candidates would fall in love with teaching early on and have a more realistic view of what will be expected of them in the classroom—and the training they need. Others might discover that they aren’t cut out for teaching and could pick a new major while changing is still relatively easy and affordable. Either way, policymakers would have a more accurate idea of how many candidates are ready to enter the teacher pipeline when they graduate.

It would be smart for more states to collect better data on teacher preparation program graduates—and to find out how many never teach. Do some take time off to travel or volunteer? Do others leave the profession altogether?

As my colleagues Alex Berg-Jacobson, Jesse Levin, and Jim Lindsay wrote in recent InformED blog, recent shortages in the teacher workforce might be just predictable variations in the employment cycle—blips that may self-correct over the next few years. Even so, policymakers and researchers need better data on how many new graduates actually enter teaching.

Jenny DeMonte is an AIR senior technical assistance consultant specializing in teacher preparation and licensure. She has worked on research and policy issues related to teacher quality and school improvement—first as a journalist and now as a researcher—for more than 20 years.