How Systems and Communities Can Partner on Goals and Measurement to Advance Equity

The different factors in a person’s life—education, geographic location, employment, health status, and social support—have a strong and interconnected impact on well-being. However, the many systems that support those factors often don’t work together.

Aligning Systems for Health, a national initiative supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), aims to address this, focusing on identifying, testing, and sharing what works to align systems to better address the goals and needs of the people and communities they serve.

AIR researchers are working on two projects funded by RWJF focused on how to use measurement to drive transformative, meaningful, and sustainable change. Below, AIR Senior Researchers Tandrea Hilliard-Boone, Ellen Schultz, and Karen Frazier discuss what they’ve learned through these projects about how systems can keep people healthy and how to use measurement as a tool to make those changes in equitable ways.

Q: What role do systems play in keeping all people healthy?

Tandrea Hilliard-Boone: Communities are made up of people with varying needs and priorities. The systems that support those communities—everything from health care, human and social services, public health, education, transportation, and justice—all have a direct influence on the health and well-being of community members. But these systems often operate in silos, which creates fragmentation in the ways that services are sought or delivered. This fragmentation makes it more likely that community members’ needs will go unmet and that they will experience worse health outcomes as a result.

Also, historically, these systems have implemented policies and practices that consistently excluded marginalized and disadvantaged communities, especially people of color. That has created longstanding inequities in health and well-being. Systems must work with each other and with community members to realign their actions to better support communities—especially those that have been historically harmed the most.

Q: How can measurement be used to promote equity?

Ellen Schultz: Organizations use measurement to set their goals and define what success looks like. It’s often linked to dollars, because it can determine how resources are allocated; it’s also used to create checks and balances on how those dollars are spent.

To promote equity, we have to identify how inequities are built into our use of measurement, and then we have to be intentional about dismantling those inequities. For instance, asking, ‘What data are we using, and where did those data come from? What biases may be built into the data? What important information do we need that those data can’t tell us?’ We need to be intentional with measurement as part of larger system transformation efforts.

Measurement is also deeply tied up in issues of power. Who owns the data? Who is collecting them? Who gets the benefit of using the data? Often, it’s those who have the power to make decisions about how systems serve communities and how resources are distributed. On the other hand, who bears the burden of generating or providing the data? Who will be most affected by the decisions that get made based on those data? Most often, it’s the people with the least amount of say in the process.

Through this work we’ve seen that an important part of changing systems is changing how those systems use measurement. Re-centering measurement around people and communities—especially those who have been excluded and marginalized—helps to recenter systems around people and communities.

Q: How do the RWJF projects use measurement to rebalance some of those inequitable power dynamics you just discussed?

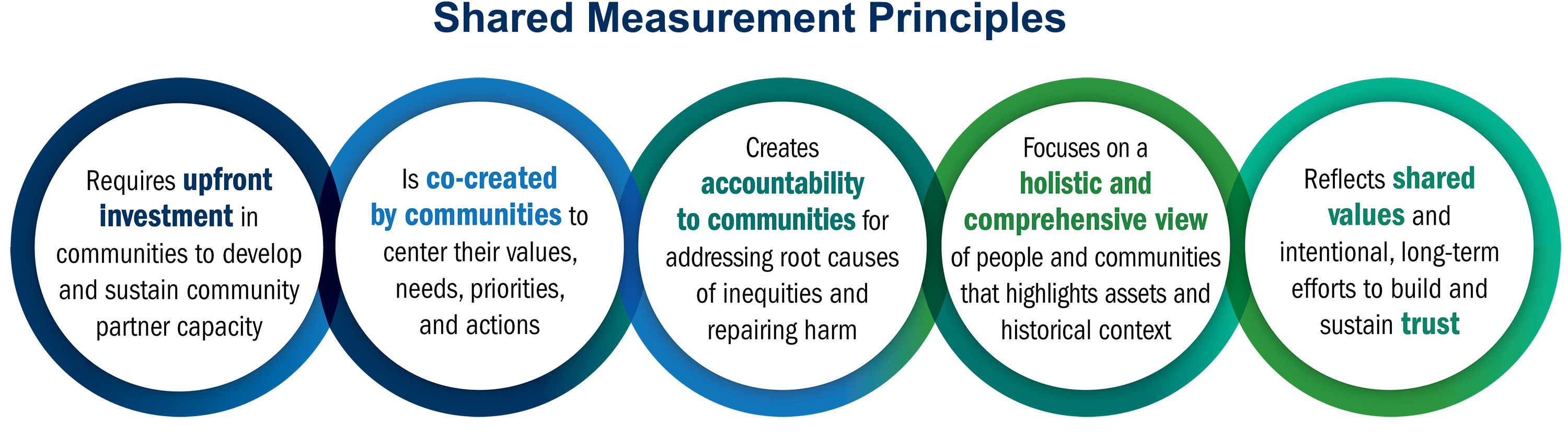

Hilliard-Boone: One project focuses on shared measurement, or using a common set of measurable goals that reflect shared priorities across systems and community members. We saw that when communities and systems use measurement together to center equity, it can lead to tangible improvements in outcomes, such as reduced hospitalizations, lower infant mortality, reduced homelessness, and greater reading proficiency.

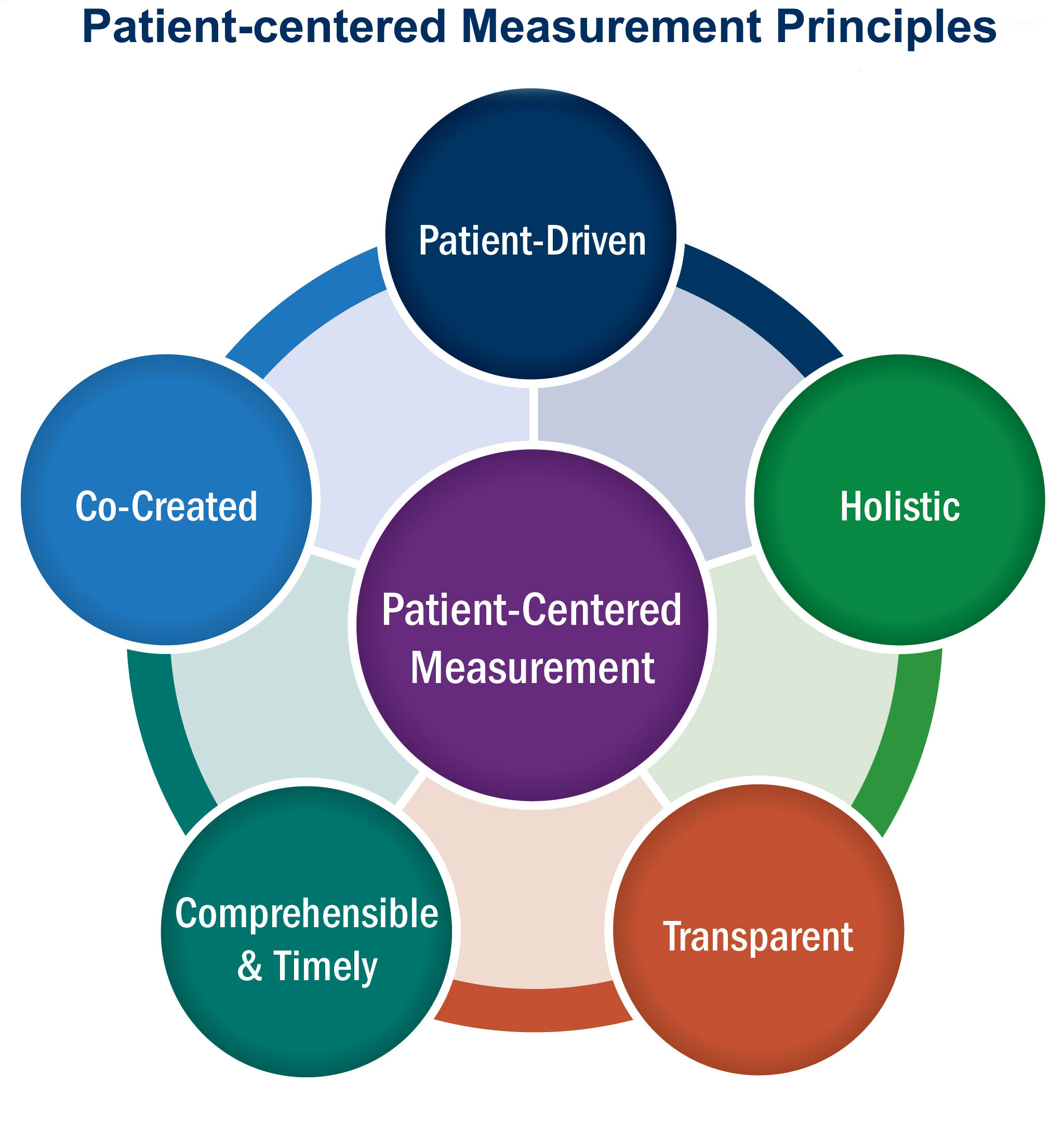

Karen Frazier: The other project focuses on patient-centered measurement, which is health care measurement driven by patients’ and caregivers’ expressed preferences, needs, and values. This project showed that the key to making measurement patient-centered is to do the work of measurement with patients and their caregivers as equal partners. This means finding meaningful ways for patients and caregivers to decide together what metrics to measure, how to measure them, who should get the results, and how to use those results.

Hilliard-Boone: We hear time and time again how critical this equal partnership is. Recently, a community member on the shared measurement project said, “We need to have a seat at the table, not on the menu.” That really stayed with me. Our work focuses on the role of people and community in the measurement process, because when they are not involved, inequities persist.

Hilliard-Boone: We hear time and time again how critical this equal partnership is. Recently, a community member on the shared measurement project said, “We need to have a seat at the table, not on the menu.” That really stayed with me. Our work focuses on the role of people and community in the measurement process, because when they are not involved, inequities persist.

Schultz: For both projects—the shared measurement work and the patient-centered measurement work—we developed principles to show what measurement looks like when it centers people and communities.

Q: What kind of initiatives are best suited to use measurement as a tool to advance equity?

Hilliard-Boone: San Antonio 2020, an initiative we studied through the shared measurement project, provides a great example. In that initiative, the city government partnered with community representatives to set a citywide goal to improve health, education, and economic opportunity. Officials used a community visioning process to identify which measures were important. They brought together community members from 11 neighborhoods, as well as city leaders. Together, they came up with 62 measures. Not only do they record all of those and share them back with the community, they also share them with 170 local organizations, who can then adapt their priorities with the community’s goals.

Frazier: In a health care context, we’ve also explored what it looks like to center measurement around people. With support from RWJF, we funded four pilot projects where we got to walk alongside four different measurement teams as they showed what patient-centered measurement looks like in practice. Each team focused on their own measurement goals, but they all included patients and caregivers as partners. These partners were treated and valued as equal members of the team. They had access to all the same information as other team members; they were developing measures and putting them into use; and their ideas were acted upon. In each case, that equal partnership made all the difference in what they produced.

For example, one team was working on dialysis care. It was a patient’s idea to apply for the grant, and he partnered with the researcher; they truly designed and led the project together. They developed a measure to reflect how well patients’ dialysis care aligns with their personal priorities. They saw that patients and their care team all benefitted from having measurement reinforce their shared goal of improving patients’ well-being.

Schultz: Ultimately, whether we’re looking at measurement efforts within one system, such as healthcare, or at efforts across multiple systems, we know that measurement can reinforce the inequitable status quo, or be a force for change, depending on how it’s used—and who’s using it. We hope to show community members, system leaders, service providers, and policymakers that they can use measurement as a tool to align decisions, policies, and practices toward equitable health and well-being. We’ve learned that an essential part of this transformative way of using measurement is doing it together in equal partnership with the people and communities we intend to serve.