In Conversation: Insights on U.S. Teachers and Principals from an International Survey

About TALIS

The 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) asked nationally representative samples of lower secondary teachers (grades 7-9 in the U.S.) and their principals questions about their backgrounds, work environments, professional development, and their beliefs and attitudes about teaching. Sponsored by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), this survey covers more than 150,000 teachers and 9,000 principals in 49 education systems.

How does the U.S. education workforce compare to other countries in terms of demographics, attitudes, and beliefs? Do they spend more time on instruction and other tasks than international educators? The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), the largest international survey of teachers and principals, provides a barometer of the profession every five years. Volume 1, the most recent release, came out in summer 2019, and Volume 2 will be released in March 2020.

AIR provides technical and substantive support to the National Center for Education Statistics for the TALIS survey in the U.S., including development of the survey, monitoring data collection, analyzing the data, and reporting and disseminating the results. AIR Principal Researchers Matthew Clifford, Ebru Erberber, and Lisa Lachlan got together to discuss TALIS 2018 key findings and policy and practice implications from a U.S. perspective. Excerpts from their conversation follow.

What do we know about the U.S. teaching and leadership workforce?

Lachlan: Through national and state surveys, we know the U.S. teaching workforce is predominantly female and white, and the TALIS survey results support that. While we don’t have information from TALIS on the gap in race or ethnicity in our teaching population—we’ll know more about this in March 2020, when Volume 2 of the survey findings is released—survey results show that fewer than 20% of our teachers are teachers of color, while our student population is now 51% non-white. Research suggests that the benefits of hiring teachers of color are manifold for both students of color and their white peers:

Lachlan: Through national and state surveys, we know the U.S. teaching workforce is predominantly female and white, and the TALIS survey results support that. While we don’t have information from TALIS on the gap in race or ethnicity in our teaching population—we’ll know more about this in March 2020, when Volume 2 of the survey findings is released—survey results show that fewer than 20% of our teachers are teachers of color, while our student population is now 51% non-white. Research suggests that the benefits of hiring teachers of color are manifold for both students of color and their white peers:

- Increased academic achievement, graduation rates, and aspirations to attend college;

- Reduced dropout and suspension rates; and

- Higher expectations of students and better preparation for all students for a diverse world.

Clifford: The principal workforce is parallel to the teacher workforce in terms of race, despite significant efforts to diversify this workforce over the past 10 years. Just as it’s important to have somebody who looks like you at the front of the classroom to learn, it’s also important that the principal reflects the community that he or she is attempting to lead—and has a deep understanding of that community, too.

Clifford: The principal workforce is parallel to the teacher workforce in terms of race, despite significant efforts to diversify this workforce over the past 10 years. Just as it’s important to have somebody who looks like you at the front of the classroom to learn, it’s also important that the principal reflects the community that he or she is attempting to lead—and has a deep understanding of that community, too.

I’m fascinated to see us getting incrementally better in terms of gender diversity among principals. In 2014, for the first time, the number of new principals who were women eclipsed the number of new principals who were men. That’s a great sign.

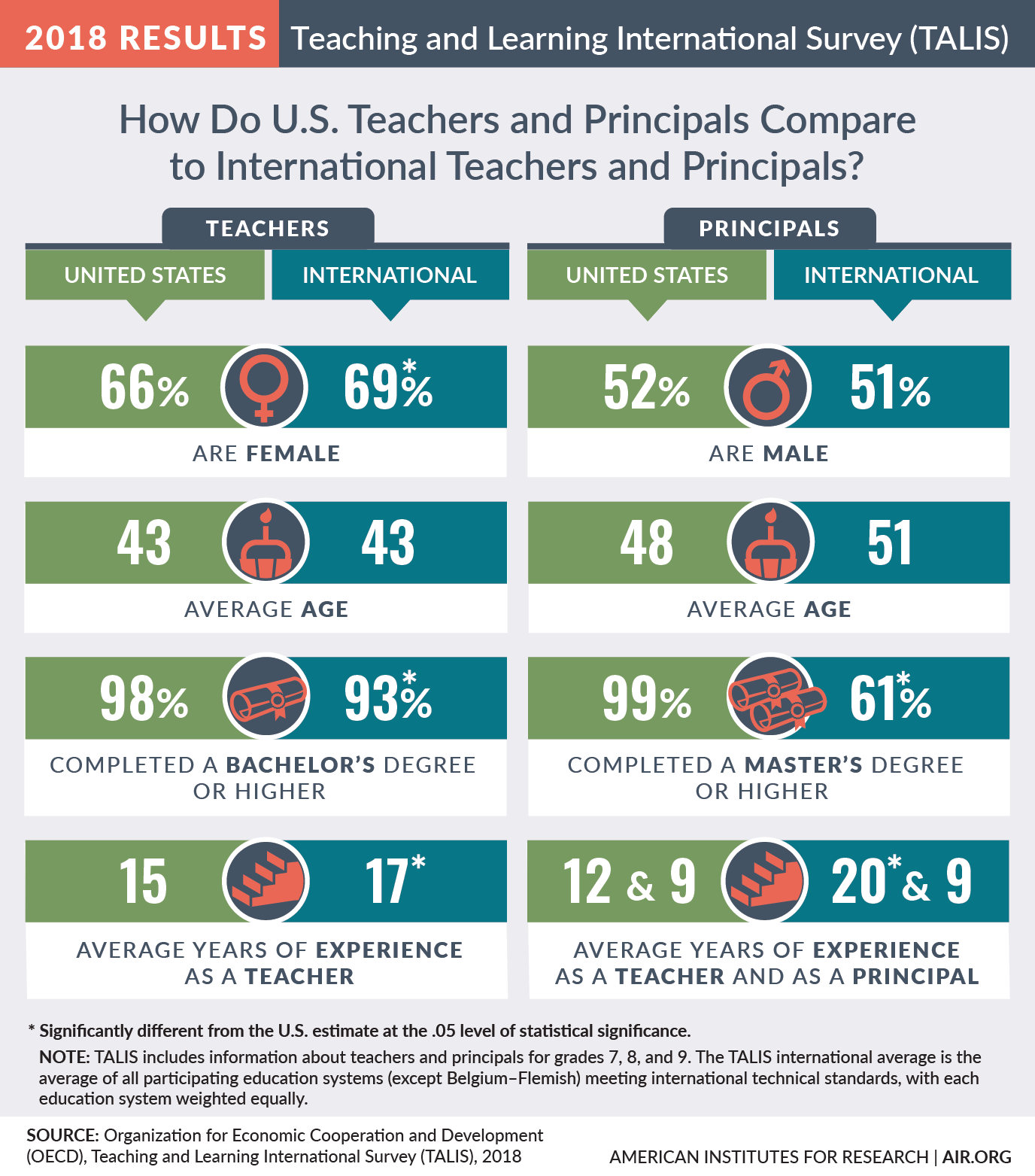

Erberber: This is striking to me as well. At the lower secondary level in the U.S., while two-thirds of teachers are women, about half of principals are women. It is also nice to see that both our teachers and, particularly, our principals are very highly educated compared to other nations. Almost all U.S. principals at the lower secondary level have completed a master’s degree or higher, compared to a little less than two-thirds internationally.

Erberber: This is striking to me as well. At the lower secondary level in the U.S., while two-thirds of teachers are women, about half of principals are women. It is also nice to see that both our teachers and, particularly, our principals are very highly educated compared to other nations. Almost all U.S. principals at the lower secondary level have completed a master’s degree or higher, compared to a little less than two-thirds internationally.

Are U.S teachers happy with their jobs? Do they think society values their work?

Erberber: Internationally, job satisfaction overall is very high, and there’s not much variability across the board in all countries. But when it comes to the perceived value of the profession in society, that varies a lot—from 5% to 92%. A little over a third of U.S. teachers indicated that the teaching profession is valued in society. That’s very telling.

Lachlan: Yes. Through teachers’ strikes and sickouts over the last year, we see these results in action. Teachers feel undervalued and rightly deserve better. We have learned that we can and must value teachers through multiple forms of recognition. The teachers who walked out in Oklahoma made it clear that this wasn’t just about themselves. They want to see students valued through the changes that state legislators and the governor are weighing to education funding. The message is: As we value our teachers, so we value our students.

Clifford: What’s interesting is the survey data indicate that pay is important. But if you look at the qualitative data, pay is not the reason that people stay. When principals decide to get into the profession, they don’t normally speak about pay. They do talk about the broader impact and the ability to change educational systems for teachers and students.

Erberber: You’re absolutely right, Matt. When asked how important certain factors were for them to become a teacher, across the board in the U.S. and in most of the other countries, teachers report that teaching allowed them “to influence the development of children” and “to provide a contribution to society.” That’s their motivation.

Lachlan: To agree with you, Matt, on this point, teachers also want expanded leadership opportunities that go beyond being an assistant principal or principal. They want opportunities to grow and lead as professionals. Having a broad set of opportunities, incentives, and supports that goes well beyond compensation can really make a difference in keeping effective teachers in the profession and making them feel more valued, which also contributes to their satisfaction.

How do U.S. educators spend their time?

Lachlan: U.S. lower secondary teachers reported spending an average each week of 28 hours teaching and a total 46 hours working. This is more than the averages for most countries in the survey. While instruction makes up most of teachers’ time, many teachers in America are tasked with a variety of work outside of the classroom. This can include prep time, grading, planning, professional development, and communication with other teachers, school administrators, and parents.

We also know that over the last decade, states and districts have experienced teacher shortages, which are in part a result of teacher attrition. And the use of teachers’ time, in particular, is part of the attrition equation. From teaching conditions surveys like the one we conduct at AIR, we know that teachers consistently report the importance of having administrators safeguard teachers’ planning time, time for collaboration, and time to maximize instructional time over the course of their week.

Teachers’ time also affects their ability to participate in professional development, with work schedule conflicts (cited by 49 percent of U.S. lower secondary teachers) and a lack of incentives (47 percent) being the most commonly cited barriers to professional development.

Learn More

Access U.S. highlights and the OECD’s international report of the TALIS 2018 Volume 1 results

Clifford: The biggest barrier to professional development for principals is also available time, according to the TALIS survey. According to TALIS, principals spend 27 percent of their time on administrative tasks and meetings; 18 percent of their time in leadership tasks and meetings; and 17 percent of their time on curriculum and teaching-related tasks. That means 62 percent of principals’ time is focused on school-related work tasks. This leaves little time for principals to engage in substantive professional development aimed at leadership practice improvement or to support teacher learning.

The TALIS data reflect other survey data on principal time allocations, and the TALIS data raises important questions for our field. If principals lack time to learn, then we have to wonder about how their time and tasks are allocated. Is there a better way to configure principal work priorities or distribute leadership tasks to allow them more time to learn?

About the Experts

- Matthew Clifford, principal researcher, focuses on improving school leadership as a means of improving instructional quality and student achievement. He manages multiple research and evaluation studies on the effectiveness of principal professional development and on principal quality. He also consults with school districts and states to design principal evaluation systems.

- Ebru Erberber, principal researcher, manages large-scale comparative studies of educational achievement. She is the project leader for TALIS and for the Trends in Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), providing expert support on survey development, implementation, reporting, and analysis to the National Center for Education Statistics.

- Lisa Lachlan, principal researcher, conducts educational policy research at federal, state, and local levels in educator equity, educator talent management, and professional learning, teacher leadership, instructional coaching, rural recruitment and retention, and educator effectiveness. She leads multiple research and policy projects on the effectiveness of workforce initiatives including: teacher preparation, induction and professional development programs.